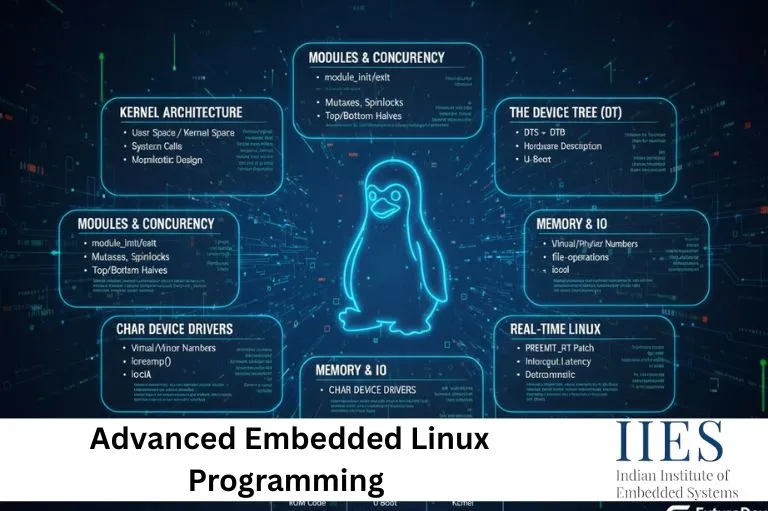

Embedded Linux Concepts

1. User Space vs Kernel Space: The Foundation of Linux

Linux operates in two clearly separated execution domains:

- User Space – where applications run with limited privileges

- Kernel Space – where the Linux kernel runs with full access to hardware

This separation is critical for system stability, security, and performance. User applications cannot access hardware directly; instead, they interact with the kernel through system calls, which act as controlled entry points.

For embedded engineers, understanding this boundary helps answer key design questions:

- Should this functionality run in user space or kernel space?

- Do we need a device driver or can a user-space interface suffice?

- How can we improve performance without compromising stability?

2. System Calls and the Linux Programming Interface

System calls are the core interface between user applications and the kernel. Functions such as:

- open()

- read()

- write()

- fork()

- ioctl()

are not simple library calls—they trigger a controlled transition from user mode to kernel mode.

Advanced Linux programming requires understanding:

- How system calls work internally

- The role of the Virtual File System (VFS)

- How ioctl() enables device-specific control operations

In embedded systems, inefficient system call usage can increase latency, affect real-time behavior, and reduce overall performance.

3. Process Management and Scheduling

Linux is a multitasking operating system capable of running hundreds of processes and threads concurrently. Embedded engineers must understand how Linux manages execution to meet timing requirements.

Key concepts include:

- Processes vs threads (task_struct)

- Context switching and its overhead

- Linux scheduling policies:

- CFS (Completely Fair Scheduler)

- FIFO

- Round-Robin

- Priority levels and real-time scheduling

In real-time embedded Linux systems, incorrect scheduling decisions can cause missed deadlines and unpredictable behavior. Engineers must know how to tune priorities and select appropriate scheduling policies.

4. Virtual Memory Management in Embedded Linux

Linux uses virtual memory to provide isolation, protection, and efficient RAM usage—even on systems with limited memory.

Important memory concepts include:

- Virtual address space per process

- Page tables and the MMU

- Demand paging

- Stack, heap, and data segments

- Kernel memory allocation:

Memory leaks or fragmentation in embedded Linux systems can cause long-term instability, making a solid understanding of memory management essential.

5. Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

Embedded Linux applications are often built as multiple cooperating processes. Linux offers several IPC mechanisms, each suited to different use cases:

- Pipes and FIFOs

- Message queues

- Shared memory

- Signals

- Semaphores and mutexes

Advanced engineers must understand when to use each IPC mechanism based on performance requirements, synchronization needs, and system complexity.

6. File Systems and Storage Internals

In Linux, everything is treated as a file, including devices. File system knowledge is critical for embedded storage design and long-term reliability.

Key topics include:

- Linux VFS architecture

- Flash-friendly file systems:

- Block devices vs character devices

- Mounting, permissions, and access control

Choosing the wrong file system can negatively impact boot time, reliability, and flash memory lifespan.

7. Device Drivers and Kernel Modules

Device drivers are the heart of embedded Linux, enabling communication between hardware peripherals and the kernel.

- Character, block, and network drivers

- Platform drivers and the Device Tree

- Probe and remove callbacks

- Interrupt handling

- Kernel synchronization primitives

Understanding driver architecture allows engineers to build efficient hardware-software integration while maintaining kernel stability.

8. Kernel Synchronization and Concurrency

The Linux kernel is highly concurrent. Multiple processes, kernel threads, and interrupts may access shared resources simultaneously.

- Spinlocks

- Mutexes

- Semaphores

- Atomic operations

- Wait queues

Incorrect synchronization can lead to race conditions, deadlocks, or kernel crashes, which are particularly difficult to debug in embedded systems.

9. Linux Boot Process and System Initialization

Understanding the Linux boot process is essential for boot-time optimization and early debugging.

A typical embedded Linux boot flow includes:

- Bootloader (commonly U-Boot)

- Kernel initialization

- Device Tree parsing

- Init system:

Embedded engineers often customize boot parameters, kernel configuration, and startup scripts to meet product-specific requirements.

10. Debugging and Performance Analysis

Advanced embedded Linux development requires strong debugging and profiling skills.

Essential tools include:

- strace and ltrace

- top, htop, and ps

- dmesg and kernel logs

- GDB and KGDB

Debugging and performance tuning are ongoing tasks throughout the product lifecycle, not one-time activities.

Advanced Linux Commands for Embedded Linux Engineers

Embedded Linux systems run with limited CPU, memory, and storage, often using BusyBox-based root file systems. Engineers must rely on lightweight yet powerful Linux commands for debugging, monitoring, and performance analysis.

1. dmesg – Kernel and Driver Debugging

dmesg displays messages from the kernel ring buffer and is essential for debugging:

- Device driver initialization

- Hardware detection failures

- Kernel warnings and errors

Example:

dmesg | tail

2. strace – System Call Tracing (User ↔ Kernel)

strace helps debug how user-space applications interact with the kernel.

Embedded use cases:

- Application startup failures

- File system and driver access issues

- Latency analysis

Example:

strace ./app

3. top – CPU and Memory Monitoring

top provides a real-time view of:

- CPU utilization

- Memory usage

- Running processes

Most embedded Linux distributions include a BusyBox version of top, making it widely available.

4. ps – Process State Inspection

ps is useful for identifying:

- Zombie or stuck processes

- Unexpected background services

- System load issues

Example (BusyBox compatible):

ps

5. free – Memory Usage Analysis

free displays available and used memory, helping detect:

- Memory leaks

- RAM exhaustion

- Cache behavior

Example:

free -h

6. mount and df – File System Diagnostics

These commands help verify:

- Mounted file systems

- Storage usage

- Read-only vs read-write mounts

Critical when debugging boot failures or flash storage issues.

7. lsmod and modprobe – Kernel Module Management

Used to inspect and control kernel modules:

- Verify driver loading

- Insert or remove modules during testing

Example:

lsmod

modprobe my_driver

8. watch – Repeated Command Execution

watch repeatedly runs a command at fixed intervals.

Embedded use cases:

- Monitor GPIO values

- Track temperature sensors

- Observe memory changes

watch cat /sys/class/thermal/thermal_zone0/temp

9. /proc and /sys – Kernel Introspection

Embedded engineers frequently inspect kernel state using:

- /proc – process and system information

- /sys – device and driver attributes

cat /proc/cpuinfo

ls /sys/class/gpio

10. chrt – Real-Time Scheduling Control

chrt sets real-time scheduling policies and priorities.

chrt -f 80 ./rt_app

Conclusion

Mastering advanced Linux programming and kernel concepts is no longer optional for embedded engineers. From process scheduling and memory management to device drivers and kernel synchronization, deep Linux knowledge enables engineers to build robust, scalable, and high-performance embedded systems. As embedded products continue to grow in complexity, engineers who understand Linux beyond the surface level will be best positioned to design reliable, production-ready solutions.